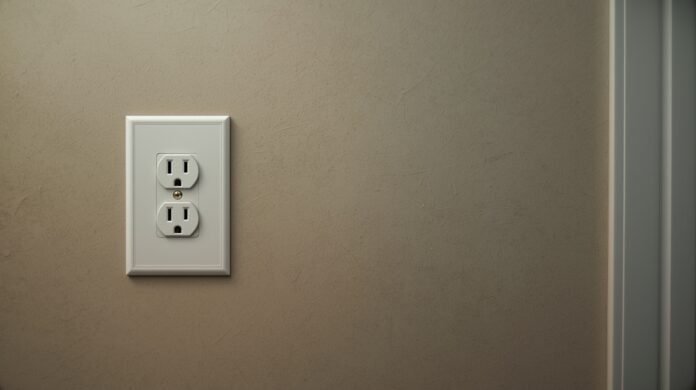

It can be unsettling to notice an outlet or light switch that feels warm to the touch—even when everything appears to be working normally and there hasn’t been a recent power outage. Many homeowners aren’t sure whether this warmth is harmless or an early warning sign.

In reality, some warmth can be normal under specific conditions, while other cases indicate electrical stress that should not be ignored.

Why Electrical Components Can Feel Warm

Whenever electricity flows, a small amount of heat is produced. Under normal conditions, that heat is minimal and dissipates safely through wiring and device components.

Warmth becomes noticeable when electrical load increases, resistance rises, or components operate near their design limits. Understanding which scenario applies is key to determining risk.

Situations Where Mild Warmth Can Be Normal

Outlets and switches may feel slightly warm when powering high-draw devices such as space heaters, hair dryers, or kitchen appliances. Dimmer switches can also feel warm due to how they regulate power.

In these cases, the warmth is typically mild, localized, and does not worsen over time once the device is turned off. For example, a dimmer that feels a little warm while running several recessed lights is often behaving normally—especially if it cools down after the lights are off.

When Warmth Signals Electrical Stress

Heat that appears during everyday use—especially with ordinary devices—often points to increased resistance or load stress inside the circuit. The most important question is whether the warmth makes sense for what the outlet or switch is powering.

If a basic phone charger, a lamp, or a TV causes noticeable warmth at the outlet face or switch plate, that is a different situation than a space heater or hair dryer. Unexplained heat often means something in the connection path is working harder than it should.

Why Breakers Often Don’t Trip

Breakers are designed to respond to dangerous current levels, not gradual heat buildup. An outlet can grow warm due to resistance while the total current remains below the breaker’s trip threshold.

This explains why heat may develop quietly, without obvious electrical failure. The underlying mechanics are explored further in how home electrical loads really work.

How Overloaded Circuits Contribute to Heat

Circuits that consistently carry heavy loads can warm connection points over time. Even if a circuit never trips, sustained stress can degrade outlet contacts and wiring insulation—especially at weak points like worn receptacles or older splices.

This is common in kitchens, garages, home offices, and older living areas where multiple devices share circuits that were not designed for modern electrical demand. A related explanation is covered in overloaded circuits without tripped breakers.

Loose Connections: A Hidden Heat Source

Loose electrical connections create resistance, which converts electrical energy directly into heat. That heat often concentrates at outlets and switches, making warmth one of the earliest detectable signs—before anything fails outright.

A realistic example: a switch might feel warm only when a bathroom fan runs, or an outlet might warm up when a vacuum is plugged in. The circuit still “works,” but the connection point is acting like a bottleneck and heating up under demand.

Why these connections develop—and why they’re dangerous—is explained in loose electrical connections in the home.

When Warm Becomes Dangerous

An outlet or switch that feels hot, not just warm, should be treated as unsafe. Warning signs include warmth spreading beyond the device, discoloration, buzzing sounds, crackling, or faint burning odors.

Heat that worsens over time or appears across multiple outlets on the same circuit is also a higher-risk pattern. If you ever feel heat plus odor, or heat plus noise, stop using the device and treat it as an escalation situation.

When to Stop Using the Outlet and Get Help

If warmth persists with normal devices, returns quickly after cooling, or is accompanied by other electrical symptoms, professional evaluation is recommended. Continuing to “test it” by plugging things in and out can increase heat stress and raise risk.

Clear stop-and-escalate guidance is outlined in when to call an electrician after an outage. Even without an outage, the same safety thresholds apply when heat, odor, or abnormal behavior appears.

Conclusion

An outlet or switch that feels warm during normal use is not always an emergency—but it is meaningful information. Mild warmth under heavy load can be normal, while unexplained heat often signals hidden electrical stress.

Paying attention to these early signals helps homeowners address problems before heat turns into damage or fire risk.